Here at myteaplanner.com, we are all about tea and tea parties, and the travel, cultural adventures and food that accompany the tea drinking traditions. With that thought in mind, I invite you to review the first two chapters of the “Tea Book” section of our website: “The Road Back to Civilization” and “The History of Tea.” Here you will be reminded that the tea plant, and the custom of brewing a refreshing beverage by pouring hot water over tea leaves, originated in China. This great and ancient country has shared not only tea, but many other civilized and artistic discoveries with the rest of the world. One of these is the Chinese New Year celebration.

This year, Chinese New Year began on January 25, and the festivities will continue for about fifteen days, until February 8. This four-thousand-year-old tradition is based on a type of lunar calendar with repeating twelve-year cycles represented by twelve “zodiac” signs named after animals. This year, a new twelve-year cycle begins with the Year of the Rat, the first animal in the cycle. If you were born in 1912, 1924, 1936, 1948, 1960, 1972, 1984, 1996, 2008 or 2020, you are a Rat. In spite of the negative connotations associated with rats in the Western world, in China people born in the Year of the Rat are perceived to be quick witted, resourceful, versatile and kind. If you think about it, rats have certainly had to develop these characteristics over the millennia to survive life on planet Earth where the dominant species, humans, hate them and want them all dead.

My father-in-law, Kiyoshi, was a Rat who managed to extricate his wife and son (my future husband Wayne) from the Manzanar concentration camp for Japanese Americans by volunteering for the U.S. Army where he was assigned as an interpreter for the War Trials held in Japan after the armistice. His youngest daughter, my sister-in-law Joyce, is also a Rat. You met Joyce in my September 2019, blog, “Lovely Lanai.” It was Joyce’s resourcefulness that brought about our Cockatoo’s move to the Four Seasons Lanai where he now enjoys a forever home in a luxurious tropical setting with his own doting full-time caregiver. And it was her kindness to her former co-workers in Lanai that generated the warm welcome we received there on our recent visit with Joyce as our guide.

The other eleven animals in the Chinese calendar in order are: Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Sheep, Monkey, Rooster, Dog and Pig.

In my family, my son David and my niece and co-author Kathleen, fondly referred to as “the twin cousins,” are both Rabbits, as they were born in the same month of the same year. The Chinese zodiac describes Rabbits as, “creative, compassionate and sensitive.” Anyone who has read Kathleen’s blogs, especially this month’s blog, “Bundt Cakes for Mourning,” on this website could easily recognize these qualities in my niece. As David’s mother, I have certainly seen these characteristics in my son. My husband Wayne and I are also zodiac twins in the Chinese system, as we were born in the same month of the same year. As Monkeys, we could be described as “smart, active, agile and adaptable to complicated living environments.” I do not see all of these qualities, especially agility, in myself, but Wayne and I are both more comfortable in complex multi-cultural environments than in homogenous social structures. This could explain our shared love for travel and diverse food, art and culture.

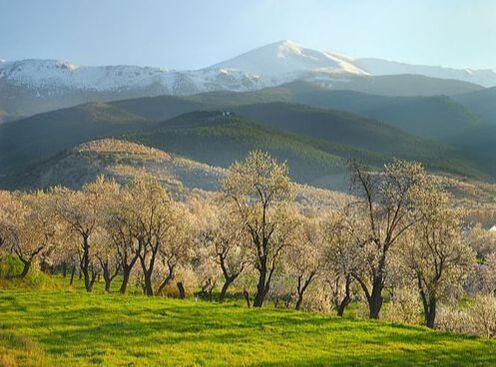

If you don’t already know your Chinese animal sign, you can look it up easily on-line just for fun. This information was crucial in the old days for arranging marriages and negotiating other inter-personal relationships. Today, in societies that encourage conformity, the animal signs remain as gentle reminders that each individual has unique gifts and personality traits. In contemporary China, the traditional New Year’s celebration continues, even though the lunar calendar was abolished in 1912 and China now begins the New Year on January 1. In 1949, the traditional New Year celebration was renamed the Spring Festival and remains a national holiday. While February may seem to be a continuation of winter, it is in February that the first signs of spring can be discerned.

It is interesting to note that the popular twelve Chinese “zodiac” signs differ from the Western zodiac of Greek and Middle Eastern origin. The great Hellenistic scientist and astrologer, Ptolemy, born in 100 CE, actually lived in Alexandria in Egypt, at that time under Greek influence. His hierarchical view of the cosmic world order and studies in astrology, the theory of the “correspondences between celestial observations and terrestrial events,” were viewed as scientific endeavors. And the twelve Greek astrological signs are based on constellations visualized by Greek astronomers. Some of these signs based on the arrangements of the stars, such as Taurus the bull and Leo the lion, are clearly associated with animals, whereas others are mythological or human, such as Virgo the maiden or Sagittarius, the Archer, a mythological centaur, half man and half horse.

Conversely, all of the members of the Chinese zodiac are animals, and none are based on either the arrangements of the stars or mythology. One might quibble that a dragon is a mythological creature and not an animal. Not so in Chinese art and tradition. In general, Chinese philosophy, literature and painting are essentially realistic even when stylized. And let me point out that dragons also appear in Western art and literature. One of my favorite works of Anglo-Saxon literature, the heroic-elegiac poem Beowulf, depicts the dragon who appears in the final episode of this otherwise realistic story in vividly specific detail, fire and all. However, each reader can decide for herself whether a dragon is, or perhaps was, in fact a real animal.

Dragons will certainly be present at this year’s Chinese Spring Festival in the form of Dragon Dances. Wherever it is celebrated, Chinese New Year is a loud, colorful and lively affair, filled with costumed dancers, loud drumming, copious amounts of fireworks, parades and, feasting, all decorated with huge red lanterns and red envelopes filled with money, passed out generously to children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews. Dragon dances and Lion dances are especially popular, as they involve vividly painted tent-like costumes worn by teams of dancers lined up in single file with the lead dancer’s head hidden by the animal’s head and the final dancer’s head under the animal’s tail. The dance team moves and gyrates in a more or less forward motion accompanied by enthusiastic drumming that lends itself to parades, or at least circumnavigations of large banquet halls or stages.

Dragon and Lion dancing often occurs as the entertainment during the New Year’s feast. This special meal, which requires seven different dishes, is prescribed to generate various kinds of good luck in the New Year, just as the loud drumming and fireworks are designed to cast away bad luck and other negative energy. The menu includes dumplings to bring wealth, fish for good fortune, sticky rice balls for family harmony, noodles for longevity and wontons, spring rolls and glutinous rice cakes for additional forms of wealth and prosperity, including career advancement.

Many other Asian countries also celebrate their own versions of Chinese New Year, including Vietnam, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and North and South Korea. Japan switched to the Gregorian calendar in 1873 during the Meiji Era when many Western ideas were introduced into Japan and now celebrates the New Year on January 1. Our family, like so many other Japanese American families, especially in Hawaii and California, celebrated the New Year on January 1. To see how Japanese Americans celebrate the New Year, turn to “A Japanese New Year’s Tea” in the “A Calendar of Tea Parties” section of this website.

Chinese New Year celebrations take place in many of the major cities in the United States and Canada, including, San Francisco, New York, Vancouver and Toronto. We will be attending the Hawaii Spring Festival in Honolulu’s Chinatown early in February. We’re looking forward to all the drumming and Dragon dancing. And although it is not part of the traditional Chinese New Year’s feast, I would like to share one of my favorite Chinese teats with you—Tea Marbled Eggs. These delicious little bites would add a surprising pop of flavor to any Afternoon Tea party or even to your Valentine’s Day gathering, nestled among the chocolates and the pink cupcakes. These tasty eggs would even fit in at your Mardi Gras celebration on February 25, as it is impossible to have too much food on Mardi Gras or at a Chinese New Year’s feast.

I found this recipe in Gourmet magazine in 2003 and have been making it ever since to rave reviews. You can find a photograph and description of this unique savory treat on our website in the “Chinese Dim Sum Tea” menu at the beginning of the “World of Tea Parties” section. This is an extra special kind of boiled egg. After boiling, the shells are cracked but not removed, then simmered in very strong tea to create a marbled effect on the egg once it is peeled. This recipe calls for dark Lapsang souchong tea, which has a strong, smoky flavor. If you prefer a milder flavor, you can use any kind of black tea, but for me, the unmatched flavor of Lapsang souchong is what makes these eggs unforgettable. And the simple mayonnaise-balsamic topping is truly the icing on the egg.

- 12 large eggs

- ¾ cup soy sauce

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- 3 cups water

- 4 Lapsang souchong tea bags

- Ice cubes for cooling the eggs

- 1 tablespoon balsamic vinegar

- ½ cup mayonnaise

Special equipment: 1 large saucepan with lid (2-3 quarts,) slotted spoon, medium sized bowl, metal spoon, small bowl, whisk, deviled egg plate or decorative platter

Makes: about 12 servings

- Place the eggs in a large saucepan and cover with about 1 inch of cold water. Bring the eggs to a rolling boil, partially covered. Remove from the heat and let the eggs stand, covered for 10 minutes.

- Partially fill a medium sized bowl with water and ice and transfer the eggs to the bowl with a slotted spoon to cool for 5 minutes. Then gently tap the shell of each egg all over with the back of a metal spoon to crack the shells lightly. Do not peel.

- Empty out the water from the saucepan, add the soy sauce, sugar and 3 cups of water to the pan and bring the mixture to a boil, stirring until the sugar is dissolved, and add the tea bags. Reduce the heat, and simmer, covered, for 10 minutes. Add the eggs, and enough water to cover them, and simmer, covered for an additional 10 minutes.

- Remove the pan from the heat and allow the eggs to cool in the liquid, covered. Refrigerate for at least 2 hours or overnight. (Unpeeled eggs can be chilled in the cooking liquid up to 2 days.) Lift the eggs from the liquid and peel. Reserve 2 tablespoons of the cooking liquid and discard the rest.

- Whisk the 2 tablespoons of reserved cooking liquid, 1 tablespoon of balsamic vinegar and ½ cup of mayonnaise in a small bowl until mixed thoroughly. (The mayonnaise mixture can be made 2 days ahead and chilled, covered.)

- Cut each egg in half, not removing the yolks. Place the egg halves in a deviled egg plate or decorative platter and top each half with a dollop of the mayonnaise mixture. Serve immediately.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed