During the month of May, like so many others who were quarantined at home against the spread of the corona virus, I spent many of those extra hours reading. And since reading has always been my favorite leisure activity, I also turned to re-reading. Two literary classics from previous centuries that I recently read once again were: The Book of Tea, penned in 1906 by Okakura Kazuo and Interior Castle, written in 1577 by Teresa of Avila. I have my friend Donna Lenahan, who lives in Los Gatos, California, to thank for these apparently diverse selections.

Apparently, Donna, in her leisure time, was cleaning out her book collection, and instead of tossing out or donating her old copy of The Book of Tea, she thought of mailing it to me, as she is familiar with this website on Afternoon Tea. Donna also volunteers to facilitate a spiritual book club in Los Gatos, where I formerly lived, and she has invited me to “read along” from a distance.

| Summer Food Tomatoes in June, orange-red and luscious, Warm to the touch and oozing With juice and seeds-- Cherries too are in their glory, Sweet and sacred on the tongue. I carry a pit in my mouth All the long afternoon While jays and iridescent pigeons Bow in the dust. Summer is the Spirit’s Feast Day When children hold the yellow corn In their two hands And every bite is Sacrament. RAH, June 13, 1994 |

It seems that the members of Donna’s book club chose to take on Teresa’s timeless classic as their spiritual food this summer.

What do The Book of Tea and Interior Castle have in common? Humility. The Book of Tea, listed in the Bibliography in the Resources section of this website, was one of the first documents to introduce the traditions and aesthetics of the Chinese and Japanese Tea Ceremonies to the English -speaking world. This small book, which can be read in a single day, was my primary source as I was preparing the introductory chapters of “The Tea Book” section of this website, especially “The Philosophy of Tea.”

The author of this remarkable little book, Okakura (family name) Kazuo (given name,) was born in Yokoyama in 1862 and died in 1913. During his lifetime, Japan’s long period of isolationism came to an end, and Japanese scholars and artists were allowed to travel to Europe and America as well as to other Asian countries. This was an exciting time of cultural exchange between the East and the West. Okakura himself traveled throughout Europe and the United States as well as China and India. He studied English and Chinese literature at Tokyo Imperial University where one of his professors was Ernest Fenollosa, the Harvard-educated scholar who also served as a cultural conduit between American and Japan.

Okakura served in a variety of distinguished positions, including the Japanese Imperial Art Commission, head of the Imperial Art School in Tokyo, founder of the Hall of Fine Arts in Tokyo, and co-founder of the Japan Art Institute. In 1910, Okakura became the first head of the Asian Art Division of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Okakura’s special gift was the ability to articulate the relationships among philosophy, culture and aesthetic values. He has been compared to the British Victorian essayist, John Ruskin (1819-1900,) who was, like Okakura, able to synthesize clearly for the general public the connections of art to nature and society.

Okakura wrote The Book of Tea in English, though Japanese was his native language. His chapter on “The Tea-Room” has always intrigued me. His emphasis on the simplicity and humility of the room reserved for tea ceremonies illuminates the influence of Zen Buddhism on the drinking of tea. He points out that, “The tea-room is unimpressive in appearance.” And “… the materials used in its construction are intended to give the suggestion of refined poverty.” To quote Okakura further, “The simplicity and purism of the tea-room resulted from emulation of the Zen monastery.” He goes on to describe the deliberately low entry door, requiring the guests to “humble themselves” by bending over as they enter. The tea-room also has a machiai, or portico, where the guests gather in respectful silence before the host invites them to enter. The guests then leave the waiting area, following the roji, or garden path, and bow reverently as they enter the tea-room. Okakura tells us that “The roji was intended to break connection with the outside world.” He includes the following poem by Kobori-Enshiu to illustrate the spiritual silence that a guest might experience walking along the roji in preparation for the tea ceremony:

Okakura points out several other aesthetic features of the tea-room designed to emphasize the precious value of humility. The lighting in a tea-room is subdued, even in the daytime, the host always cleans the room carefully before the guests arrive, but not for an antiseptic effect, but to suggest the refreshing purity of nature. The tea-room is also essentially empty of all furniture except the tokonoma, or alcove, into which a painting, flower arrangement or other work of art could be added by the host to suggest the season or theme of the tea gathering. Okakura also uses the word “unsymmetrical” to describe one of the key features of Japanese aesthetics, specifically influenced by the tea ceremony. He asserts that the Western habit of displaying collections and other valuable objects symmetrically on “mantelpieces and elsewhere” in the home is disturbing in its busyness and repetition. It also suggests a lack of humility, as it is a form of showing off one’s wealth. Furthermore, an excessive number of objects in a room leaves nothing to the guest’s imagination and can be somewhat suffocating. Okakura concludes that “The simplicity of the tea-room and its freedom from vulgarity make it truly a sanctuary from the vexations of the outer world.”

I believe that Teresa of Avila would have agreed with him. Her masterpiece, Interior Castle, written in 1577, describes the serenity, peace and joy available to any person who embarks on the journey of silence through interior prayer and contemplation. And she points out that this journey is impossible without the gift of humility. In one of my favorite lines in her entire book, Teresa proclaims, “While we are on this earth, nothing is more important to us than humility.” Teresa practiced this principle in her own life, as she faced many challenges, particularly at the hands of authoritarian men, yet she managed to achieve remarkable milestones in the development of human spirituality, achieved through skillful diplomacy and genuine humility.

Born in Avila in Spain in 1515, Teresa de Cepeda y Ahumada entered the Carmelite order at about the age of twenty over her father’s objections. Gifted with leadership skills, Teresa went on to establish seventeen new convents and became a central figure in the Catholic Reformation, taking place within the Catholic Church while the Protestant Reformation was occurring throughout Europe. Her own order had become a rather comfortable place of refuge for aristocratic ladies and their servants to escape from the restrictions of family expectations. By the time Teresa joined the once austere Carmelite order, the nuns were enjoying a luxurious lifestyle, wearing jewelry and inviting gentlemen over for visits and parties. Teresa originated the Carmelite Reform, guiding her sisters in a restoration of the original contemplative and austere life of the order.

Change is almost never welcome, and essentially all of Teresa’s efforts were met with strident opposition. However, buoyed by her faith, resourcefulness and yes, humility, she not only wrote several books, including her autobiography, that remain classics today, but she founded the Order of the Discalced (barefoot) Carmelites, a religious community still active worldwide following “our vocation of reparation,” by praying silently for the sins of the human race. The Carmelites, as reformed by Teresa, continue to live in cloistered convents in silence and poverty, subsisting only on public charity. In 1622, Teresa was canonized a saint, and in 1970, she was proclaimed the first woman Doctor of the Church. Teresa’s convent in the lovely hill town of Avila still stands, a place of pilgrimage, and a timeless monument to “refined poverty.”

Okakura Kazuo and Teresa of Avila were both born into wealthy and aristocratic families. Yet both chose to focus on the quiet beauty of simplicity and solitude. In the newly transformed world where we find ourselves today, we have been offered the opportunity to embrace change and accept a far humbler life than we may have been led to expect. No one knows if we will ever fully return to our previous culture of extroverted consumerism. Will we once again spend our weekends in loud bars and restaurants with crowds of friends, purchase season’s tickets to sporting events and concerts, embark on luxurious vacations and travels and devote hours of our time to shopping for designer clothing in busy malls? Some of us may simply, like the Carmelites and the practitioners of the Tea Ceremony, stay at home and welcome the quiet elegance that every sunrise brings.

This economical summer Afternoon Tea menu is designed to celebrate the luscious fresh produce that is available in June throughout Asia, Europe and the Americas: tomatoes, cucumbers and my favorite fruit—cherries. Our menu is based on ancient foods that have provided pleasure and nutrition for the human race for centuries. None of the ingredients are costly or difficult to find, and the recipes are all very simple. As we prepare for this humble afternoon tea, our energy will be free to focus on the aesthetic potential of a summer’s day. With inspiration from our friends Kazuo and Teresa, we will have time to find serenity and quiet as we clean our home, prepare the food and look to nature for artistic inspiration to help us create a humble but welcoming environment for our Japanese-Spanish fusion tea with friends.

The free recipes for Summer Tomato Sandwiches, Egg Salad Sandwiches and Cream Scones can be found in the Tea Menu Basics chapter of the Tea Book section of this website. Just add half a teaspoon of Spanish Smoked Paprika to spice up the Egg Salad. The Cucumber Namasu and Cold Tofu (Hiyayakko) can both be found in the Japanese New Year’s Tea in the January Calendar section of the Tea Book.

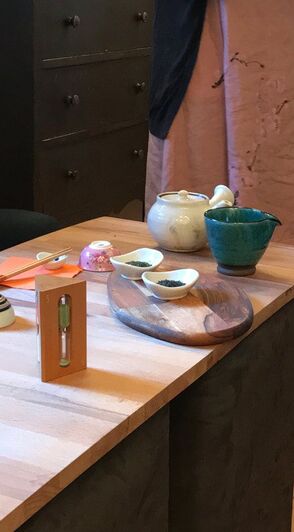

For décor, let nature be your guide. Try to avoid excessive decoration or repetitive patterns. And feel free to use unmatched serving pieces and linens, as long as they feel harmonious together and strike a summer mood. You might choose a single flower in a container that is pleasing to you as the artistic focal point for your gathering. As Okakura Kazuo points out, “In joy or sadness, flowers are our constant friends.”

Beverages

Japanese Green Tea

Home-Made Lemonade

Savories

Summer Tomato Sandwiches on White Pullman Bread

Egg Salad Sandwiches with Spanish Hot Paprika on Brown Pullman Bread

Cucumber Namasu

Hiyayakko (Cold Tofu with Fresh Ginger and Bonito Flakes)

Spanish Olives

Scones

Cream Scones with Butter and Seville Orange Marmalade

Sweets

Honey-Vanilla Yogurt and Home-Made Almond Granola Parfaits with Fresh Cherries

Bittersweet Chocolate Ghirardelli Squares

- 2 teaspoons olive oil

- 3 ½ cups old fashioned oats

- 1 cup almond butter

- 1 heaping cup whole almonds

- ¼ teaspoon kosher salt

- 6 tablespoons pure maple syrup

- 1 cup dried cranberries (or raisins, dried blueberries, dried cherries or a combination)

Preheat oven to 350° F

Special equipment: Large foil-lined baking sheet, large mixing bowl, fork, rubber spatula, wooden spoon, measuring spoons and 1-cup measure, wire rack, cannister with a secure lid for storing

Serves: about 12 generous servings

- Preheat the oven and coat the foil-lined baking sheet with 2 teaspoons of olive oil.

- In a large mixing bowl, combine the oats, almond butter, whole almonds, kosher salt and maple syrup. Use a fork to distribute the almond butter evenly into the mixture.

- Spread the oat mixture evenly over the prepared baking sheet and bake for 20 minutes, stirring with a wooden spoon after 10 minutes to allow the granola to toast evenly.

- After the first 20 minutes, sprinkle the dried cranberries over the granola and carefully stir them into the mixture. Bake for an additional 10 minutes for a total of 30 minutes of baking.

- Remove the granola to a wire rack to cool, stirring gently with a wooden spoon. When the mixture is completely cooled, store it in a cannister or large jar with a tightly fitting lid.

To Make Yogurt and Granola Parfaits with Fresh Cherries:

A parfait is simply a dessert in which the components are layered attractively so the guests can see the colors and contrasting textures of the ingredients as they eat. For this reason, it is best to use small, clear glasses or sherbet dishes to highlight the beautiful red cherries, creamy white yogurt and crumbly golden granola in this simple yet radiant dessert.

Start with about 1 cup of ripe red cherries, about a pint (2 cups) of whole vanilla honey Greek-style yogurt and about 2 cups of Home-Made Almond Granola. Cut the cherries in half and pit them, reserving 4-6 whole cherries with the stems still attached—the number of individual parfaits you plan to make. Place about 2 tablespoons of honey vanilla yogurt in the bottoms of 4-6 small dessert containers. Although I have recommended glass containers, feel free to choose any small bowls, not necessarily matching, that appeal to you. Add a few cherry halves on top of the yogurt and sprinkle about 2 tablespoons of granola over the cherries. Layer the yogurt, cherries and granola again one or two more times until the bowls are almost full. Top each parfait with a whole cherry. Chill until ready to serve. Enjoy any remaining cherries, yogurt and granola for breakfast or snacks.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed