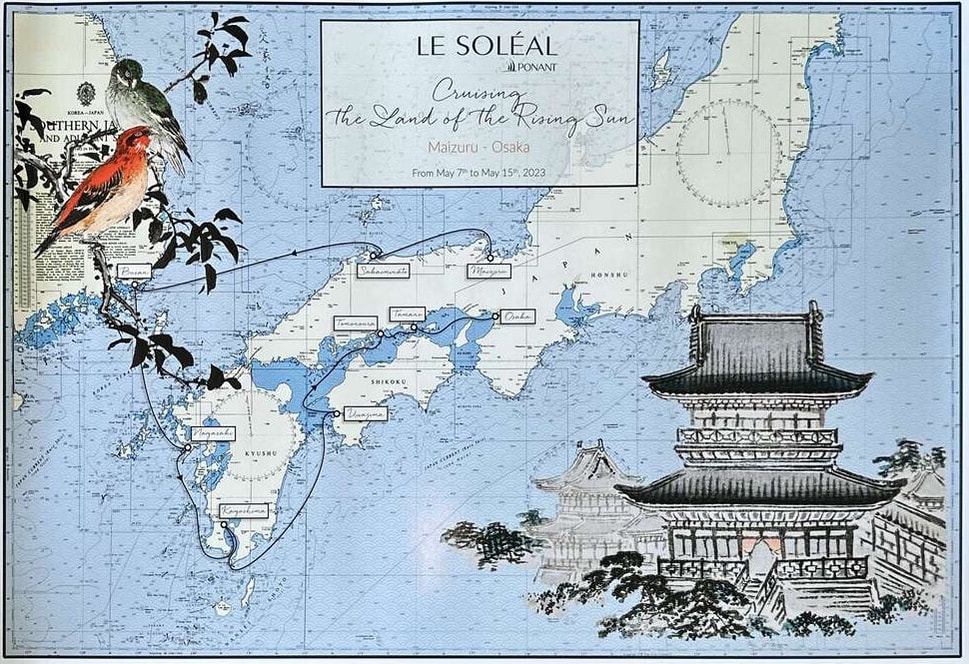

On Le Soleal, we enjoyed the fresh and elegant cuisine created by the French chef, and we were intrigued by the itinerary, which took us from the southern end of Honshu on the Sea of Japan to the islands of Kyushu and Shikoku, even farther to the south. We were delighted to discover that traditional Japanese arts and crafts are not only being preserved in the big cities like Osaka and Tokyo, but are thriving in small, lesser-known locations as well. Along our journey south along the waterways, we were treated to a traditional Japanese dance performance, introduced to Taiko drumming, and welcomed by local children offering us gifts of hand-made paper cranes in the ancient art of Origami, as we disembarked our ship. The old-fashioned art of hospitality is still alive in these more remote and rural areas of Japan, where a small sized cruise ship docking in the local harbor is cause for celebration for the entire community.

On this small ship voyage, we also visited the places where Europeans first interacted with the Japanese in the 1500s, and it was interesting to see the many ways that foreign influence has affected Japanese life while ancient traditions continue to flourish.

Yasugi is the hometown of the museum’s founder, Zenko Adachi, a local man who made a fortune in real estate in Osaka and gave back to his community by building this tasteful and elegant museum and garden in 1970. The large garden, which includes waterfalls and borrowed distant mountain landscapes, has been ranked the best garden in Japan for the past twenty years.

The museum’s well-curated collection is gracefully presented in refined, spacious and quiet rooms, featuring Japanese works in various media from the late 1800s through the Twentieth Century. One entire section of the museum is dedicated to the ceramic artist Kitaoji Rosanjin, who owned a restaurant. His pieces are arrestingly beautiful—traditional yet modern. And several of his ceramic creations that were on display were accompanied by photographs of the dish, bowl or plate being used to serve delicious looking Japanese food. Rosanjin clearly understood that the visual presentation of Japanese food is an art form in itself.

I was impressed by the fact that much of the more recent art in Japan, especially the paintings, maintain the traditional aesthetic principles of asymmetrical composition, focus on nature, spontaneity and subtlety, yet convey a modern feeling. The museum also had a tea ceremony room and a Japanese style lunchroom adhering to these same principles of melding modernity with tradition. My husband Wayne and I stopped in the little lunchroom for Japanese tea and red bean and mochi ball soup, just like Wayne’s mother Misae used to make for all of us back home.

In the medieval town of Matsue, only a short distance away from lovely Daikonjima, we visited one of the oldest samurai castles in Japan, still standing in its original wooden construction, having survived fires, earthquakes and wars since it was completed in 1611 by the first daimyo of Matsue, Horio Yoshiharu. Registered as a National Treasure of Japan, this watchtower style hilltop castle in the center of Matsue, is a gem worth exploring. We climbed all the way to the top of this impressive fortification, eight floors up polished wood ladder-like stairways. It was breathtaking to look down at the panoramic view of the city, the surrounding farms, and the cedars, filled with herons.

Le Soleal carried us south to the historic city of Nagasaki on the island of Kyushu, another city on a hill with splendid views.

The cable car in Nagasaki is called the Ropeway, and it carries visitors to the top of Mount Inasa for an unforgettable view of the city and all the many harbors, rivers and small islands that surround it. Nagasaki was the first Japanese city to welcome European visitors, and the Portuguese were the first to arrive. The explorers Antonio Mota and Francisco Zeimoto landed on the island of Tamegashima in 1543. In 1549, the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier arrived in Kagoshima, also in southern Kyushu. Japan opened the port of Nagasaki for trade with the Portuguese in 1571 but expelled them in 1639 for unfair trading practices and coercive missionary zeal, both of which were offensive to the samurai system of values. The Dutch, however, were allowed to trade with the Japanese, but only from an artificial island outside the port of Nagasaki. This partnership continued from 1641 to 1854, a few years before Japan’s isolationist policy ended in 1868 with the Meiji Restoration.

We decided to have lunch at the observatory on top of Mount Inasa. I thought the food was surprisingly good for a tourist destination. We ate something called “Turkish Rice,” an odd name because the food was not Turkish, but apparently it was intended to represent the east-west fusion of Nagasaki cuisine based on the decades of trade with the Portuguese and the Dutch during the Tokugawa period of samurai rule. I was served two curry flavored “samosas” in a green salad, a tasty creamy white onion soup with garden fresh green peas and a vegetarian rice dish tasting a lot like risotto with mushrooms and lots of black pepper. Dessert was a light and airy strawberry cake.

Southern Kyushu is a sub-tropical area very different in climate and vegetation from the more northern region of Honshu where Tokyo is located. Like France and California, Japan is a place where individual towns and regions have their own food specialties, known as terroirs in French. Factors such as climate, terrain and soil or water conditions affect the quality of the foods produced in these regions. Just as Gilroy in California is famous for garlic and Watsonville produces the best strawberries, Kyushu’s warm humid climate produces Japan’s best oranges, yuzu (another citrus fruit,) melons and sweet potatoes. Japanese tourists from the northern areas of the country love to load up on local specialties to take home. While we were in Kyushu, we enjoyed Orange Pound Cake, a European invention adapted for Japanese tastes and beautifully packaged in tiny individual servings to take home. We also delighted in the sweet potato flavored soft-serve ice cream available only in Kyushu.

If you would like to create a lovely dessert for your family reminiscent of both the balmy orange groves of Kyushu and the Portuguese traders who first visited Kyushu in the 1500s, I recommend Bolinhos de Laranja, the luscious little orange cakes featured in my April 2021 blog on this website.

After leaving Nagasaki, Le Soliel took us to the lovely tropical island of Kagoshima, the medieval estate of the Shimazu samurai clan, and on by ferry boat to Sakurajima (literally Cherry Blossom Island) to view the active volcano that was smoking the day we were there. Though “shima” or “jima” at the end of a Japanese place name indicates that this place is an island, Sakurajima is no longer an island, as the most recent volcanic eruption in 1914 spewed enough lava to re-attach Sakurajima to Kyushu. The two ferry boats that run for twenty-four hours a day from Kagoshima to Sakurajima are not just there to serve tourists. They are also trained for emergency evacuations, as this volcano could erupt again at any time.

A large amount of black smoke was emanating from the volcano when we were there, and the stairs and pathways leading up to the observation area were all covered with black and powdery soot. There are also lots of hot springs in the area around the volcano, and naturally many onsen, (traditional Japanese hot springs inns.) We were escorted to a place where visitors could soak their feet and lower legs in the hot springs mineral water while sitting on ground-level wooden benches. It was so invigorating, and my feet and skin felt wonderful afterwards.

Our ship sailed away at twilight for Uwajima on the island of Shikoku, nestled in the waterways between the southern tip of Honshu and Kyushu. When we entered Uwajima’s harbor at dawn, the local fishing boats with colorful streamers flying from their masts, followed along beside us to welcome us to their community. Everywhere in Japan, people were kind and hospitable, but on Shikoku, we received more signs of welcome, friendship and gratitude than anywhere else in Japan. Our destination was the town of Yoshida, which the Yoshida samurai clan ruled in the Seventeenth Century. Their descendants still live in the area, and they have created an “Open Air Museum,” called Kuniyasuno Sato, where they have reconstructed the original village with locals dressed in period costumes along the lines of Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia. We received a very gracious welcome with cups of the local mandarin orange juice, which was almost miraculously delicious! The town had moved some of the houses and other buildings from nearby locations and completely renovated them to reclaim their original appearance.

The town elder was there to greet us with a little speech in Japanese. He was elegantly dressed like the feudal lord from the 1600s. There was also a master craftsman on the premises, a traditional carpenter who is a designated “living treasure of Japan.” He demonstrated how to plane a cypress board just using a wood and steel hand tool so that the board appeared to be polished or lacquered. Using this amazing technique, none of the houses in the village needed to be painted. Neither did they require nails to assemble the floors and walls. A young man dressed in full samurai armor and regalia, including an authentic helmet and sword, was also part of the “cast of characters,” along with a woman in a charming summer kimono. The entire “village” lined up and waved to us as we boarded the bus back to Le Soleal.

Our final stop along the southern waterways was the town of Kurashiki on the southernmost tip of Honshu near the city of Okayama. Kurashiki is a beautiful historic town filled with four-hundred-year-old buildings as well as willow-lined canals reminding us of Venice.

Kurashiki was the home of the Ohara family who became wealthy producing textiles, especially denim and jeans. Fortunately, the Ohara clan shared their wealth with the community through philanthropy by funding and supporting hospitals, research institutes and the arts. Ohara Magosaburo, who lived from 1880 to 1943, was an enthusiastic patron of the arts, including the European artists of his era, especially the Impressionists. Magosaburo also mentored a local Japanese artist, Kojima Torajiro, who lived from 1881 to 1929. Mr. Ohara funded Kojima’s travels to Europe to study Western art, which strongly influenced his work. Ohara also commissioned Kojima to purchase numerous paintings in Europe and bring them back to Japan, including El Greco’s Annunciation, and works by Courbet, Pissarro, Matisse, Gaugin, Renoir, Modigliani, and a splendid painting of waterlilies which Claude Monet, who loved Japanese art, personally selected to be sent to Japan. Kojima also acquired works of art from Ancient Egypt and the Near East.

Upon Kojima’s death in 1930, Ohara founded the Ohara Museum of Art to house and display the artworks that Kojima had collected as well as Kojima’s own works, which are on a par with the finest of the French Impressionists.

Ohara chose to construct the museum in the Classical Greek architectural style, as it is a tribute to Western art. Charmingly surrounded by gardens and sited near a canal where baby swans follow their elegant parents through the quiet waters, the Ohara Museum of Art, the oldest museum of Western art in Japan, resembles an ancient Greek temple with its symmetrical marble staircase, classic Ionic columns and triangular pedimented roof. Of all our discoveries in our sojourn among the southern waterways of Japan, the Ohara Museum of Art was the crowning jewel.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed